The unprecedented agreement gives five tribes more input in the management of Bears Ears National Monument in Utah

By Maxine Joselow

Updated June 20, 2022 at 12:44 p.m. EDT|Published June 20, 2022 at 11:41 a.m. EDT

The Biden administration has reached a historic agreement to give five Native American tribes more say over the day-to-day management of a national monument in Utah, marking a new chapter in the federal government’s often-fraught relationship with tribes.

The Interior Department’s Bureau of Land Management and the U.S. Forest Service signed the cooperative agreement on Saturday with five tribes that have inhabited the region surrounding Bears Ears National Monument for centuries: the Hopi Tribe, the Navajo Nation, the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, the Ute Indian Tribe of the Uintah and Ouray Reservation, and the Pueblo of Zuni.

“Today, instead of being removed from a landscape to make way for a public park, we are being invited back to our ancestral homelands to help repair them and plan for a resilient future,” Carleton Bowekaty, co-chair of the Bears Ears Commission and lieutenant governor of the Pueblo of Zuni, said in a statement.

Bureau of Land Management Director Tracy Stone-Manning said in a statement that the agreement is “an important step as we move forward together to ensure that tribal expertise and traditional perspectives remain at the forefront of our joint decision-making for the Bears Ears National Monument.”

The move comes as Interior Secretary Deb Haaland — the first Native American to serve as a Cabinet secretary — works to repair the federal government’s relationship with tribes, which has been tarnished by instances of federal officials removing Indigenous peoples from their ancestral lands.

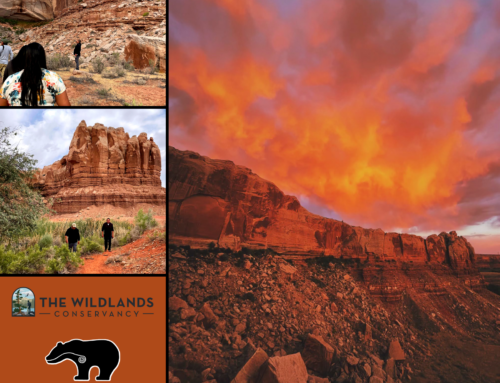

Humans have inhabited the southeast corner of Utah for 13,000 years, carving arrowheads from stone, farming corn, painting images on rocks and creating communities on the mesa tops. But in recent years, Bears Ears has been at the center of a fierce political battle over America’s public lands.

In 2016, President Barack Obama established the Bears Ears National Monument, named for a pair of tall buttes that resemble the top of a bear’s head peeking over a ridge. His proclamation recognized the land’s “profoundly sacred” meaning for many Native American tribes.

Eleven months later, in December 2017, President Donald Trump shrank Bears Ears by more than 1.1 million acres, or about 85 percent. While conservative lawmakers cheered the decision, activists protested outside the White House and in Utah.

In October, President Biden used executive orders to protect 1.36 million acres in Bears Ears — slightly larger than the original boundary that Obama established. The orders also reversed Trump’s cuts to the 1.87 million-acre Grand Staircase-Escalante monument. And they reestablished the Bears Ears Commission, which comprises one elected officer from each of the five tribes.

Pat Gonzales-Rogers, executive director of the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition, a consortium of all five tribes, said Saturday’s agreement could set a precedent for arrangements with other tribes and communities of color across the country.

“Some of the things that we’re doing are portable to many other entities in Indian country, and in some ways they can provide a paradigm for other BIPOC [Black, Indigenous and people of color] groups,” Gonzales-Rogers said in an interview.

In the coming weeks, the five tribes plan to submit a land management plan for Bears Ears to the Bureau of Land Management. The agency will then incorporate the tribes’ recommendations into its own plan, which could take up to 18 months to finalized.

Federal officials, including at the Interior Department, have often had fraught dealings with the nation’s 574 federally recognized tribes across the Lower 48 and Alaska. In the late 19th century, federal officials removed Native Americans from their ancestral lands, including from Yellowstone, the nation’s first national park.

In 1983, Interior Secretary James G. Watt blamed the problems on U.S. reservations on Indigenous culture. “If you want an example of the failure of socialism, don’t go to Russia,” Watts said. “Come to America and go to the Indian reservations.”

Haaland, a member of the Pueblo of Laguna, has sought to address this troubled legacy since taking the helm of the Interior Department last year. In May, she announced plans to meet with survivors of Indian boarding schools across the country in a tour called “The Road to Healing.” Native American children who attended these schools were forcibly taken from their families to be “assimilated,” and those who died were often buried in unmarked graves.

See the article at The Washington Post