Opinion: Postpone vacations in already-vulnerable tribal communities to stop the spread of COVID-19

These natural landscapes are first and foremost the homelands of Indigenous peoples. Regions such as the Grand Canyon, Bears Ears and Chaco Canyon are considered sacred, and Native communities still inhabit or return to the regions that their ancestors once occupied. Today, Tribal lands are often either included in or immediately adjacent to popular tourist attractions. For many Tribal businesses, tourist activity is essential for their incomes, and as a result, have been hard hit by shutdowns.

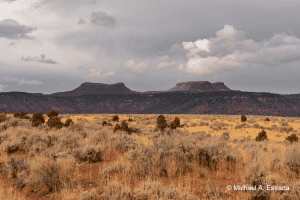

Additionally, Indigenous cultural sites in areas such as these are extremely vulnerable now that there is less monitoring of on-the-ground activity to deter vandalism and looting. Many sensitive locations rely heavily on public outreach and education to teach visitors about respectful behaviors to practice around sacred ancestral sites. Bears Ears, located in southeast Utah, is an area of extreme concern as it lacks comprehensive protection and is considered one of biggest cultural heritage sites in the world.

(The Bears Ears landscape — named for two twin peaks that look over what is now southeastern Utah — is the Indigenous homelands to the Diné, Ute, Paiute, and Pueblo peoples. Tribes have long advocated for its protection as it is one of the most endangered cultural heritage sites in the world. Photo Credit: Michael A. Estrada)

As such, traveling through Tribal lands be detrimental to the health of Tribes and the landscapes they work to protect. Due to historical, racial, socioeconomic and cultural factors, Indigenous communities are more at-risk for the rampant spread of COVID-19. Consistently underfunded Tribal health care services struggle to test and slow outbreaks. High rates of chronic illnesses in Indigenous communities — diabetes, heart disease, obesity — make it easier for the virus to spread.

In addition to inadequate health resources, there is the issue of access. In some areas, running water is not readily available, which can make washing hands difficult. Native households are more likely to be intergenerational, with children growing up in the same space as their grandparents. Routine cultural and communal gatherings are a foundational component of Indigenous lifeways. These factors make addressing the virus difficult and complicated.

Tribes have implemented strict safety measures to protect their people — especially their elders. In Indigenous communities, elders are the caretakers of oral teachings, songs, stories and other irreplaceable information. They hold Traditional Knowledge that is paramount to their cultural foundation and survival, and Native families are working tirelessly to keep them safe. For Native communities, lockdown and social distancing measures are not merely an inconvenience, but a necessity to ensure their continued existence.

(Community members of the Zuni Pueblo, located in New Mexico, organize supplies donated to their Emergency Mobile Pantry. Packages are delivered to elders, families, and others in need as the Tribe has issued stay-at-home orders.)

We need to stand in solidarity and respect Tribes’ efforts to combat COVID-19 by avoiding trips through and/or stopping in Tribal lands. It’s likely that many Tribal governments will enforce isolation measures, roadblocks, and distancing rules long past state guidelines. Such measures will continue to uproot normal life by impacting communal gatherings and ceremonies as well as prove increasingly difficult for their own economies. Despite these disruptions, Tribal communities continue to carry out intense safety protocols to ensure the survival of their people and culture.

We should remain attuned to Tribes’ requests and needs and seek out opportunities to aid their relief efforts. Let’s demonstrate the power of interconnectedness by postponing road trips and outdoor activities in areas surrounded by Indigenous communities.

Indigenous peoples are not unfamiliar with hardship and resilience. As a people, they have survived and persevered through disease and epidemics since the arrival of colonists to their homelands hundreds of years ago. While Tribal communities are facing new challenges presented by COVID-19, they are meeting them with the same diligence, creativity and wisdom of their ancestors.

The Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition represents a historic consortium of sovereign Tribal nations — the Hopi Tribe, Navajo Nation, Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, Pueblo of Zuni, and Uintah and Ouray Ute Indian Tribe — united in the effort to conserve and protect the Bears Ears cultural landscape.

…

Click here to view the original publication.